What is Amebic Colitis?

Introduction

Causes and symptoms of amebic colitis

Associated complications of amebic colitis

Pathophysiology of amebic colitis

Detecting amoebic colitis

Treatment of amoebic colitis

References

Further reading

Amebic Colitis is caused by the anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan Entameba histolytica. This bacterium infects the mucosa in the colon and accounts for 100,000 deaths annually.

The parasite infects 10% of the world’s population. Diagnosis of amoebic colitis is often difficult as gastrointestinal symptoms are non-specific and can appear similar to colon diseases. There are several complications of amoebic colitis; these include perforation of the intestines, hemorrhages, strictures or obstructions, and peritonitis.

Image Credit: Chutima c/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Chutima c/Shutterstock

Causes and symptoms of amebic colitis

Amebic Colitis is commonly found in homosexuals, institutionalized or immunocompromised people, recent immigrants, and travelers to an endemic area. The symptoms of amoebic colitis arise from epithelial cell penetration and can vary widely but generally include:

- Liver abscess

- Colonic granulomatous bumps that can appear as carcinomas

- Dysentry with diarrhea and rectal bleeding, which causes misdiagnosis of IBD (this symptom set (accounts for ~ 90% of clinical cases). In the clinical setting, patients usually present after one to two weeks of experiencing watery stools with blood or mucus, lower abdominal pain, tenesmus (sensation of being unable to empty the bowels), and fever. Weight loss and extreme weakness can result from dysentery, which may be experienced for months

Read Next: What is Ulcerative Colitis?

Read Next: What is Ulcerative Colitis?

Associated complications of amebic colitis

The amoeba can be spread by ingesting an amoeba cyst. These cysts can appear in contaminated food and water; moreover, transmission is possible by fecal-oral self inoculation and during oral-anal sexual contact. The incubation period of the parasite is between one and 14 weeks.

In severe cases, the onset of amoebic colitis can be sudden and includes profuse diarrhea and fever. This subsequently leads to dehydration and imbalances in electrolytes. Amoebic colitis is subsequently characterized by worsening ulcers caused by the invasion of the parasite. These produce flask-shaped ulcerations in the caecal or colonic mucosa.

Chronic amoebic colitis is often difficult to distinguish from irritable bowel disease; as such, the disease must be ruled out before treatment with corticosteroids for IBD.

Pathophysiology of amebic colitis

Entamoeba histolytica has a replicative trophozoite stage and dormant cyst stage. A trophozoite is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of some protozoa. This parasite is difficult to distinguish from other forms of non-pathogenic E. dispar and E. moshkovskii. However, 10% of the world's population is estimated to carry one of these three microorganisms. Of all individuals carrying these amoebae, 90% carry the nonpathogenic E. dispar and 10% carry the pathogenic E. histolytica. Subsequently, 10% of those that carry the amoebic colitis-causing organism develop invasive disease. The remainder can clear the disease within a year.

There are several characteristics of Entamoeba histolytica epidemiology and the rate of fecal-oral transmission. These include:

- Lack of requirement for dual or multiple hosts

- A bias towards human hosts (rarely appearing in animal reservoirs)

- The ease at which asymptomatic carriers can spread the disease

- The highly infectious nature of robust cysts which are shed in feces

- The robustness of cysts means they can continue to survive in sewage and contaminated water for extended periods

- Ease of transmission through food and water contaminated by feces

- Resistance to chlorine present in drinking water supplies; this is the primary means of disinfection of water, and therefore renders this ineffective

Image Credit: Orawan Pattarawimonchai/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Orawan Pattarawimonchai/Shutterstock

Detecting amoebic colitis

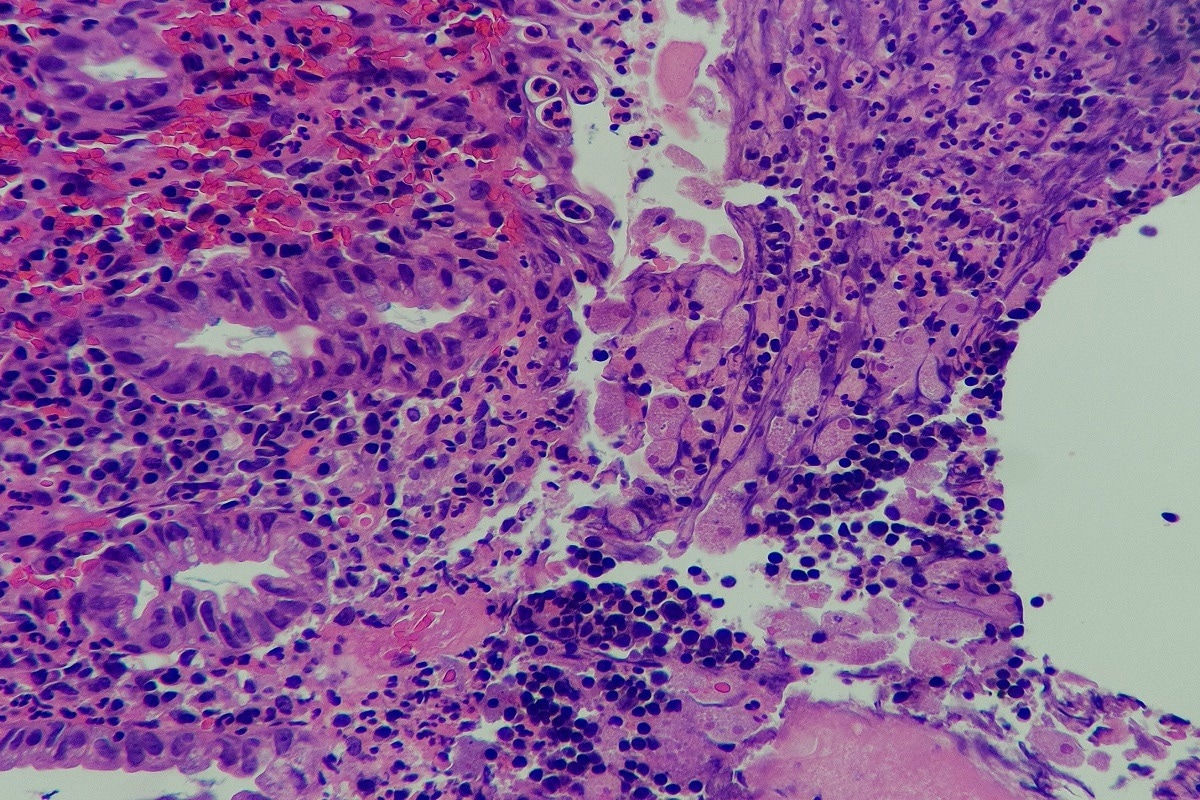

Colonoscopy and microscopic examination of biopsies are the gold standards for diagnosing amoebic colitis. The trophozoite contained within ulcers can be seen under a microscope. Patients with diarrhea are likely to have E. histolytica present in the stool. As the cecum and ascending colon are affected, histological examination of the ulcers shows flask-shaped protozoa. in severe cases, the ulcers will merge and present as ulcerative colitis.

Amoebic liver abscesses can be detected by ultrasonographic or radiographic testing. Serological methods to detect the bacterium can be used; in 90% of cases, the results are positive where patients have an extraintestinal disease. Although antibody levels increase after the tissue is invaded, these antibodies do not confer protection.

Antibodies are also not able to detect the difference between past and current infection; this is because antibodies can remain several years after infection. Tests can detect the presence of E. histolytica antigen in the stool and are more useful in confirming a current infection. Point-of-care testing is useful for rapid diagnosis of E .histolytica, and these methods are currently being developed.

Treatment of amoebic colitis

Treatment options for amoebic colitis include lumenal agents (iodoquinol, diloxanide furoate, and paromomycin) combined with tissue ambecides (nitroimidazole/metronidazole, nitazoxanide, erythromycin, and chloroquine). Luminal agents alone are effective against organisms present in the intestinal lumen but do not show effectiveness against invasive diseases. Therefore, combination with an amoebicide is useful to prevent relapse. For patients with liver abscesses, non-surgical aspiration may be necessary.

To enhance treatment and prevention, a better understanding of amoebic colitis is necessary. Precautions can be taken to minimize the risk of contracting the disease, including explaining the risks of eating raw vegetables and fruits and drinking contaminated water. With drug treatment, patients are likely to be cured. However, in the absence of drug therapy, reduced quality of life and death are common.

Image Credit: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

References

- Taherian M, Samankan S, Cagir B. Amebic Colitis. [Updated 2020 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542237/.

- Rachel M. Chalmers. (2014) Chapter Eighteen – Entamoeba histolytica. In: Steven L. Percival, Marylynn V. Yates, David W. Williams, Rachel M. Chalmers, Nicholas F. Gray (Eds.) Microbiology of Waterborne Diseases (Second Edition) (pp 355-373). Academic Press.

Further Reading

- All Abdominal Pain Content

- What is Abdominal Pain?

- What Causes Abdominal Pain?

- Chronic Functional Abdominal Pain (CFAP)

- Functional Abdominal Pain Syndrome (FAPS)

Last Updated: Aug 5, 2022

Written by

Hidaya Aliouche

Hidaya is a science communications enthusiast who has recently graduated and is embarking on a career in the science and medical copywriting. She has a B.Sc. in Biochemistry from The University of Manchester. She is passionate about writing and is particularly interested in microbiology, immunology, and biochemistry.

Source: Read Full Article