What is Influenza?

Skip to:

- Prevalence & Incidence

- Symptoms

- Causes

- Treatment, Prevention & Control

- COVID-19

Influenza (or the flu) is an infectious respiratory condition caused by influenza viruses. Influenza is different from the common cold. Unlike the common cold, influenza (flu) can lead to serious health complications such as pneumonia, otitis media, and death.

Although influenza can affect anyone at any age at any time of the year, it circulates at higher levels and can cause outbreaks during the winter in the northern hemisphere.

Young children, older people, and people with pre-existing health conditions are most at risk of complications from flu infection.

Prevalence & Incidence

Within the USA and the UK, the peak season for influenza typically is between October and April, whereas countries along the equator are typically at risk all year round. In between each 'flu-season,' subtle mutations occur to influenza viruses, known as (mild) antigenic drift, that can lead to epidemics.

Pandemics (global epidemics) can occur when a new subtype of the influenza virus (type A) emerges when there is an abrupt major antigenic change to the virus antigens, this is called antigenic shift.

Compared to annual local epidemics, which are less severe and have a better prognosis due to milder mutations, global pandemics occur with massive changes to each virus subtype.

Human populations who have not been exposed to this subtype before are vulnerable to infection as their immune system does not recognize the new subtype. This leads to a faster and more aggressive spread of influenza.

Examples of global influenza pandemics include the 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus), 1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus), 1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus) and the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus) which is estimated to have caused between 100,000 and 400,000 deaths globally in the first year alone.

Symptoms

The initial symptoms of influenza are similar to that of the common cold, and unlike the common cold, which is gradual, influenza can emerge quite rapidly a one to three days after infection with the first symptoms typically being that of chills and aches.

Symptoms include:

- Fever (sudden onset) as well as chills

- Dry cough, sore throat, and hoarseness

- Muscular pains and aches: including headache and earache

- Watering reddened eyes, face, and mouth

- Nausea (feeling sick) and loss of appetite

- Runny and blocked nose, or nasal congestion (more common in common colds)

- In some cases, diarrhea or abdominal pains

The symptoms of influenza are a mixture of the symptoms of a common cold (but more severe), with that of the symptoms of pneumonia, fatigue and muscular pain.

Typically, a cough coupled with a fever is a good indication of influenza. In healthy individuals, the flu can last up to 2 weeks and can be naturally fought off by the body's immune system. It is estimated that between 30 to 50% of influenza infections have no symptoms at all.

A definite diagnosis can be made by using the rapid molecular assay test, which is able to quickly diagnose influenza by taking a nasal swab within the first four days of symptomatic onset. These assays test for viral antigens (of the viruses discussed below) and can provide results within 30 minutes.

Causes

Influenza is caused by the influenza virus; of which 3 main types affect humans: Influenza types A-C. These viruses are airborne and therefore spread in the air by coughing or sneezing; ejecting approximately half a million virus particles, less commonly contact of contaminated surfaces, may also lead to infection.

Influenza A and B are responsible for seasonal influenza, whereas Influenza C only causes mild symptoms. Influenza A is also responsible for more serious global pandemics.

Influenza A is primarily hosted in wild aquatic birds that typically cause 'bird-flu' in wild and domestic bird populations as well as the occasional human influenza pandemic.

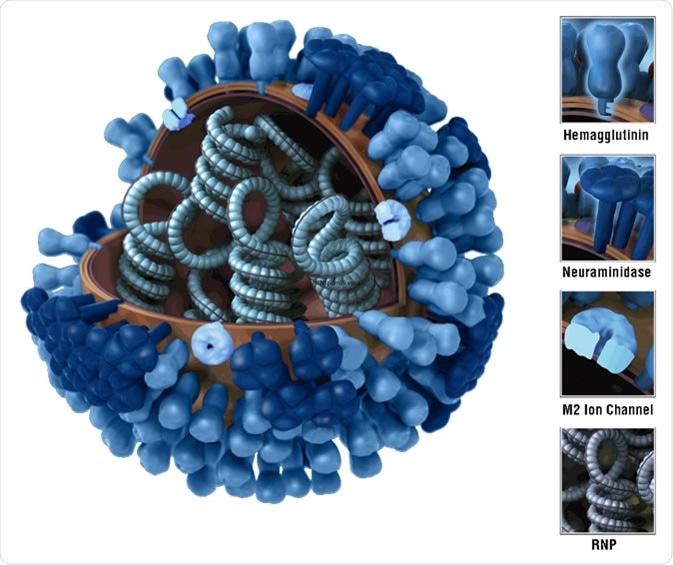

Influenza A viruses are categorized by subtype based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). The different types of H and N are numbered and there are 18 different H subtypes and 11 different NA subtypes. It's the combination of these proteins that identify which subtype an influenza A virus belongs to, e.g., H1N1 (Spanish Flu 1918 and 2009) or H5N1 (Bird Flu 2004).

Influenza A is prone to a high rate of mutation and is incredibly genetically diverse, hence the reduced immunity in humans throughout life.

Influenza B only is almost exclusive to humans. It has only one subtype and although there is antigenic drift resulting in different strains of Influenza B there is no antigenic shift so humans typically have a higher level of immunity to it from childhood. Influenza C also has one species that can affect humans, dogs, and pigs.

Usually, Influenza C causes mild infections in children. Although a fourth group, influenza virus D was identified in 2011, it appears to be limited to cattle and pigs although there is concern that it could become an emerging disease threat for cattle-workers in the future.

Once a person has become infected, depending on the type and destructive properties of the strain, the infection may take place along different parts of the respiratory system, or in other tissues.

Typically, humans only possess particular enzymes that are able to allow influenza viruses to infiltrate cells within the throat and lungs (cleavage of hemagglutinin) and therefore cannot infect other tissues or organs, however, more severely virulent strains such as H5N1 can also bind to receptors much deeper within the lungs, and as such are able to cause more severe symptoms including pneumonia – but is less easily 'coughed-out', compared to those that bind to the upper respiratory tracts which tend to be less severe.

Treatment, Prevention & Control

Those that are diagnosed with influenza need to isolate themselves and avoid close contact with others in the effort to limit the spread of the virus.

Basic preventative strategies such as washing one's hands with warm water and soap, the use of tissues when sneezing, and blowing one's nose as well as not stockpiling used tissues may be a good start in limiting spread.

The best course of action for someone who has influenza is to rest, sleep, keep warm, drink plenty of fluids, take OTC (over the counter) medications such as paracetamol or ibuprofen to treat pains, aches and fever symptoms. Other OTC medication mixes can also be taken but must not be taken in conjunction with paracetamol as they typically contain it.

As influenza is viral, antibiotics will have no effect on the infection or alter the outcome in any way, unless there is a secondary bacterial infection after influenza infection. The only real treatment of influenza are antivirals, especially within the first 48 hours of infection, however, many virus strains are resistant to conventional antivirals.

The main antivirals used include oseltamivir (75mg twice daily for 5 days) or zanamivir (10mg as 2x 5mg puff inhalations, twice daily for 5 days). These antivirals can also be used as chemoprophylaxis agents to prevent or reduce the severity of influenza if infected (in high-risk groups). Healthy individuals may fight off the infection naturally within a couple of weeks, however, high-risk groups including young children, pregnant women and the elderly may be given antivirals.

Particular groups of people may be eligible for the free flu vaccine in the UK on an annual basis in the run-up to winter. These include those over the age of 65, pregnant women, obese individuals, carers and home workers, children of primary school age, or those with chronic illnesses.

It is important to stress, and the 'flu-jab' does not guarantee protection from seasonal influenza. However, it reduces the risk of infection and/or complications of infection in risk groups.

A new influenza vaccine needs to be made every year for each influenza season based on the most common variants of that or the previous year due to the high mutation rates of the viruses. It is also the reason why 100% of protection cannot be guaranteed.

COVID-19

Influenza and COVID-19, the illness caused by the new coronavirus, are both infectious respiratory illnesses. Although the symptoms of COVID-19 and the flu can look similar, the two illnesses are caused by different viruses. COVID-19 is caused by one virus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2.

Sources:

- NHS.uk (2020). Flu. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/flu/

- Ghebrehewet et al, 2016. Influenza. BMJ. 355:i6258 https://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i6258

- Moghadami, M (2017). A Narrative Review of Influenza: A Seasonal and Pandemic Disease. Iran J Med Sci. 42(1):2-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28293045

- Greenbook of Immunisation. Chapter 19: Influenza

Further Reading

- All Influenza Content

- Types of Influenza

- Influenza Immunization

- Influenza Epidemiology

- Influenza Prognosis

Last Updated: Mar 23, 2020

Written by

Osman Shabir

Osman is a Neuroscience PhD Research Student at the University of Sheffield studying the impact of cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer's disease on neurovascular coupling using pre-clinical models and neuroimaging techniques.

Source: Read Full Article