What is Apathy and Why Does it Occur?

Skip to:

- What is Apathy?

- Neurobiology of Apathy

- Apathy in Depression & Schizophrenia

- Apathy in Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

What is Apathy?

Apathy is defined as a loss of interest in relation to social or emotional situations (a state of indifferent mood). Apathy is presented as a lack of feeling, interest or any particular concern about a specific situation, or life in general.

Though many people may have short periods of apathy at some points in their lives (i.e. shrugging off disappointment, or feelings of ‘cannot be bothered’), apathy in the medical sense is considered a long-term syndrome, typically associated with certain mental states or disorders. Specific symptoms of apathy include:

- Absence or suppression of emotion, feeling, concern or passion

- Lack of motivation (to do or complete anything) – weaker form of avolition

- Lack of sense or purpose – but not depression (i.e. worthlessness and hopelessness)

- Sluggishness/low energy levels and passiveness

- Detachment from life and personal events – very common in dementia

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), optimal health includes ‘being of a state that maximises one’s potential for physical and mental/emotional growth’. Apathy therefore falls short of WHO’s definition of optimal health.

Apathy is different from a reduction in emotional display or expression (emotional blunting) where individuals fail to express their feelings or emotions, though emotion itself is not intrinsically reduced. Apathy and avolition, a severe lack of motivation/initiative or reduced drive to do or complete tasks, have some overlap. Although with apathy, if there were to be a real threat or genuine consequence, people will often change their behaviour temporarily. People with avolition (common in schizophrenia and some forms of depression) may not change their behaviour at all.

Neurobiology of Apathy

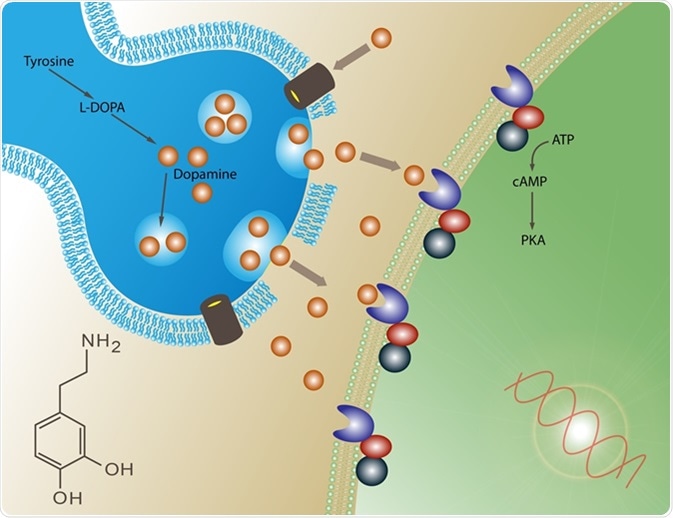

Motivated behaviour is initiated and modulated by reciprocally interconnected brain regions. These include a network of the medial frontal lobe and striatum. Disruption to these connections and projection from this network can be associated with the development of apathy. A decreased metabolism within the striatum is associated strongly with an increase in apathy scores. Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter involved in these brain circuits and is heavily involved in regulating motivation (see Chronic Inflammation, Dopamine and Motivation Levels).

The basal ganglia, of which the striatum is a part of, are involved in ‘rewards’ or drive. The orbitofrontal cortex within the prefrontal cortex is known to integrate networks from the striatum to give us a representation of the value of a behaviour or reward. Disruption to these networks may lead to apathy as there is a mismatch between motivation and reward or drive, leading to the ‘unwillingness to work’, or ‘lack of concern or sense of purpose’.

Apathy therefore is not ‘normal’ and prolonged apathy should be considered as a neurological or psychiatric symptom, most likely associated with an underlying brain disease.

Apathy in Depression & Schizophrenia

People often mistake apathy for depression, and vice versa. Apathy may be a symptom of depression, though apathy in itself is distinct, as apathetic people do not typically display symptoms of prolonged low mood and hopelessness. As discussed below, apathy maybe a more important hallmark of neurodegenerative disease than depression, though often there is much comorbidity of the three (apathy, depression and dementia).

People with schizophrenia often have high levels of blunted emotions (flat affect), and also high levels of apathy (shared negative symptoms with depression). In both schizophrenia and depression, patients undergoing treatment are often aware of their apathy, and cite it to be one of their major symptoms. On the other hand, patients with dementia (discussed below), are often unaware of their apathy.

Common treatments for depression include a class of anti-depressant called SSRI (serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor). Counterintuitively, SSRIs are known to actually cause apathy in patients with milder forms of depression, as an unwanted side effect. As apathy is not usually a main symptom of depression (unless in apathy-depression), studies have shown that up to 20% of SSRI users experience apathy. Though the mechanisms behind this are still largely unclear, it is though that serotonin-mediated dopamine modulation in areas of the prefrontal cortex may be causing apathy in such cases.

Apathy in Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

Apathy is more common in people with dementia than in healthy older people. Around 50-70% of people with dementia have apathy, whereas only 2-5% of older healthy people are apathetic. Of the dementias, it is more common in frontotemporal dementia. This can in part be attributed to the disruption to the normal network between medial frontal lobe and the striatum.

In Alzheimer’s disease, apathy is thought to be attributed to higher tangle and plaque loads, whiter matter hyperintensities, reduced blood flow (hypoperfusion) in specific regions involved in apathy, including frontal-subcortical networks. Apathy is also usually one of the first symptoms to present in Alzheimer’s disease along with memory deficits.

Functional neuroimaging studies have revealed that apathy in Alzheimer’s patients is due to a reduced metabolism (as measured by glucose metabolism) in the orbitofrontal cortex and the ventral striatum, confirming that these brain regions are involved in apathy. Furthermore, across all forms of dementia, hypometabolism in the ventral tegmental area is seen to produce apathy. These functional and structural changes are also seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease who display apathy (a common feature of Parkinson’s).

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are sometimes used to manage Alzheimer’s disease symptoms; however, they are not curative or disease modifying.

It has been shown that such medications can be successful in reducing the levels of apathy in some dementia patients. Furthermore, more natural therapies such as Gingko biloba special extract EGb 761® (see Alzheimer’s disease and Gingko biloba) may also reduce apathy levels in Alzheimer’s patients. Though for both, much larger sample sizes with controlled-trials are needed to explore this definitively. What may work for some patients may not work for others, and these medications may gradually lose their potency over time.

Other conditions in which apathy may be present include post-traumatic stress disorder, hypo-/hyper-thyroidism, chronic fatigue syndrome, Huntington’s disease, Pick’s disease, autism, ADHD and heavy users of opiates.

In summary, apathy is the state of indifferent mood characterised by the loss of interest, motivation or pleasure in everyday activities.

Apathy in the chronic sense is not a healthy part of ageing, or life, and can be attributed to many neurological and psychiatric conditions including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia. Dysfunctional brain circuitry involved in producing motivated behaviour is thought to be implicated in apathy.

As apathy is usually comorbid with other conditions, specific treatments such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s may improve apathy, though the effectiveness of such treatments is variable.

Sources:

- Heron et al, 2018. The anatomy of apathy: A neurocognitive framework for amotivated behaviour. Neuropsychologia. 118(Pt B):54-67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28689673

- Alzheimer’s Society (UK), alzhiemers.org.uk (2019). www.alzheimers.org.uk/…/factsheet_depression_and_anxiety.pdf

- Theleritis et al, 2017. Pharmacological and Nonpharmacological Treatment for Apathy in Alzheimer Disease : A systematic review across modalities. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 30(1):26-49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28248559

Further Reading

- All Psychiatry Content

- What is Psychiatry?

- Personalized Medicine and Psychiatry

Last Updated: Sep 23, 2019

Written by

Osman Shabir

Osman is a Neuroscience PhD Research Student at the University of Sheffield studying the impact of cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer's disease on neurovascular coupling using pre-clinical models and neuroimaging techniques.

Source: Read Full Article