The functional organization of cells in the retina is shaped by natural panoramic environments

Existing neuroscientific models of the visual system suggest that it represents the visual world just as a camera would, encoding the positions of different objects similarly. An animal’s surrounding environment, however, constantly changes, and these changes could also influence the processing of visual information.

Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology in Austria and LMU in Germany recently gathered evidence supporting this hypothesis and showing that the organization of neurons in the mouse retina is affected by panoramic (i.e., wide view) visual statistics, such as non-uniformities in light levels. Their findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, could significantly contribute to the present understanding of the visual system and its evolution.

“A key feature of every living organism is adapting to its environment to survive,” Maximillian Jösch, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Medical Xpress. “Such adaptations should also occur in the computations performed by the brain, for instance to extract relevant and dismiss less critical information. We set out to test this idea by taking advantage of the most prominent visual changes observed systematically in nature: the gradient of light intensity and contrast levels from the ground to the sky to ask if the mouse visual system evolved to consider these constraints.”

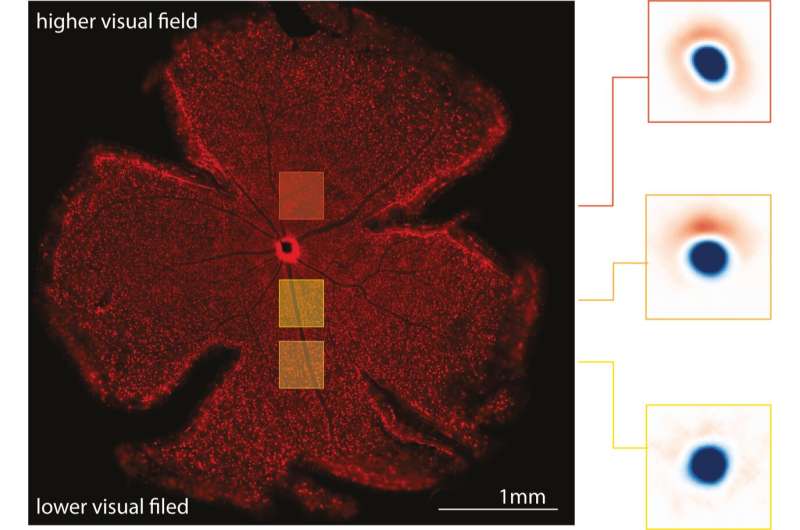

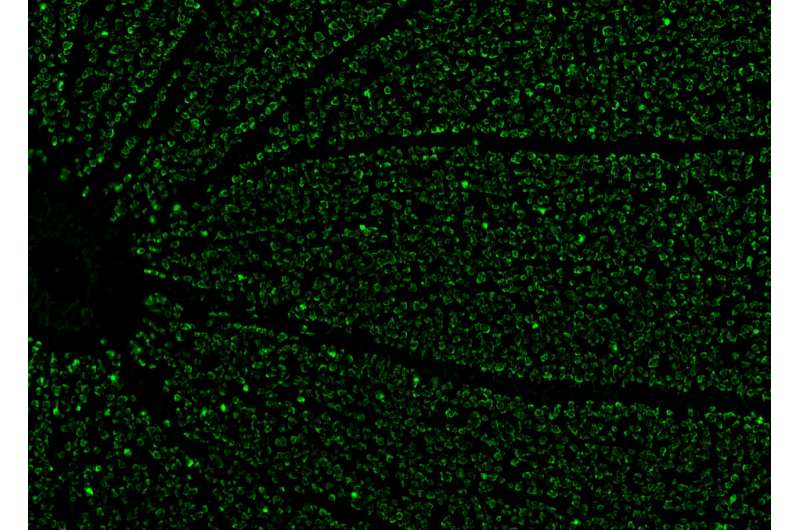

To examine the organization of sensory space that activate each neuron in the mouse retina (receptive fields) in relation to the scenes that mice are observing, Jösch and his colleagues developed a new optical imaging technique. This technique allows them to measure and track the activity of thousands of neurons in a single retina simultaneously.

“Our optical method works as follows: when a retina neuron is active, sending electrical pulses to the brain, ions flow inside the cell, e.g., calcium,” Jösch explained. “We can visualize that activity by adding a fluorescent indicator in each neuron. When calcium flows in, the fluorescence changes. These changes in fluorescence can be recorded with a sensitive camera, and with that, we can infer how the neuron responds to different visual stimuli across the entire retina.”

The researchers conducted their experiments on extracted mice retinas. Like that of most mammals, the mouse retina does not include the small area known as the fovea, a small slump in the retina that allows humans and other primates to see at high definition. The fovea, which makes up less than 1% of the entire human retina, is known to play a key role in the visual perceptions of which humans are more conscious. The remaining 99% of the human retina also contributes to visual perceptions, from which many appear to be unconscious processes. Thus, from a human centric perspective, this study focuses on the processing happening the latter 99%/.

Jösch and his colleagues found that the computations performed by neurons in the mice retina changed depending on the panoramic visual statistics of what that part of the retina usually sees during daylight. This supports their initial hypothesis that the visual system is not inherently homogenous and is in fact adapted to the external environment.

“To our surprise, we found that retinal neurons are more likely to inform the rest of the brain when a stimuli change is unexpected,” Jösch said. “Importantly, the unexpected depends on where the neuron looks, either the sky or the ground. Thus, retina circuits systematically adapted their properties from the lower to the higher visual field to represent the world more efficiently.”

Overall, the findings gathered by this team of researchers suggest that the panoramic structure of natural scenes affects the organization of different processing strategies in different regions of the retina. This expands previous models of the visual system, highlighting its adaptive and dynamic nature.

“We usually assume that the visual system is homogenous, or in other words, that the visual world is represented like a camera, measuring each position similarly,” Jösch added. “However, our natural surroundings are not similar; they systematically change from ground to sky. Thus, a system that evolved to live in nature should consider this. Our results indicate that living organisms’ visual system has adapted to cope with natural constraints to improve the efficiency of their neuronal code.”

In the future, the recent work by Jösch and his colleagues could inspire other teams to further examine how panoramic statistics or other visual elements shape cell organization in the retina to refine our understanding of vision in general.

“We are now exploring how similar adaptations change when changing the context, for example, when adapting to different light levels occurring during the day or at night,” Jösch added.

More information:

Divyansh Gupta et al, Panoramic visual statistics shape retina-wide organization of receptive fields, Nature Neuroscience (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01280-0

Journal information:

Nature Neuroscience

Source: Read Full Article