New Research Criteria May Help Predict Progression to CTE

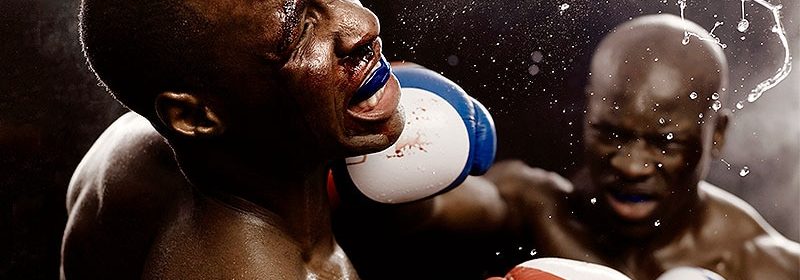

New research criteria appear to accurately identify athletes in sports such as boxing or martial arts who will go on to develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

Developed in 2021 by the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the aim of the development of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) criteria was to provide a way to diagnose the condition in living people.

This new study, which was published online June 28 in Neurology, is the first longitudinal assessment of the criteria, which researchers say is a small but important step toward determining whether criteria developed only for research purposes may one day be appropriate for clinical use to diagnose TES early and to potentially prevent progression to CTE.

Investigators found that among fighters who met the criteria for TES, reaction times were significantly slower and patients had lower cognitive test scores than those who didn’t meet the NINDS criteria. Brain volume decline was also significantly greater and occurred at a faster rate among those with TES.

Dr Brooke Conway Kleven

“We are seeing clinically that they are having cognitive changes, behavioral changes, overall functional changes, but we’re also seeing that a lot of the imaging changes are likely preceding the clinical changes that we saw,” said lead investigator Brooke Conway Kleven, DPT, PhD, a research analyst with the School of Public Health and Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “This group of people who meet the criteria for TES are having a more rapid deterioration in certain brain regions of interest over time.”

CTE Link

The NINDS criteria set out specific factors that must be present for TES diagnosis.

These include exposure to repetitive head impacts from contact sports, military service, or other causes; core clinical features of cognitive impairment and/or neurobehavioral dysregulation; a progressive course; and clinical features that are not attributable to any other neurologic, psychiatric, or medical condition. All these criteria must be met for a TES diagnosis.

The criteria, which offer significant improvements over earlier guidelines, were developed on the basis of retrospective reports from relatives of athletes whose condition was diagnosed post mortem.

For this study, investigators collected neurologic and cognitive information from 130 active and retired fighters who are participating in the ongoing longitudinal Professional Athletes Brain Health Study.

Participants underwent brain scans and cognitive testing at the beginning of the study. They then underwent annual brain scans and cognitive tests over a period of up to 6 years.

Slower Reaction Times, Lower Cognitive Function

Using the NINDS criteria, a panel of four clinicians diagnosed TES in 52 fighters, or 40% of the total cohort. Those with the condition were more likely to be older (mean age, 45.9 years, vs 41.3 years; P = .0046), retired (81.6% vs 38.0%; P < .0001), and to have significantly lower education (P = .0066).

They were also more likely to report boxing as their sole form of fighting and to report a greater number of fights than those without TES.

Slower reaction times and lower scores on all the cognitive tests were more common among the TES-positive group after adjusting for factors that might affect test scores.

Analysis of MRI results showed significant differences between groups in brain volume. Among patients who were positive for TES, brain volumes were significantly smaller with respect to the thalamus, putamen, hippocampus, white matter, gray matter, and corpus callosum and were significantly larger with respect to the lateral and inferior lateral ventricles.

In addition, among fighters with TES, the annual rate of decline in brain volume was faster in the lateral and inferior lateral ventricles and the hippocampus. Changes in that region were striking; for TES patients, volumes were 385 mm3 smaller than for those without the syndrome. Those with the syndrome were losing volume at an average rate of 41 mm3 per year faster than those without the syndrome.

“This gives us good insight to future studies because we can look at these specific areas of the brain before somebody starts exhibiting clinical symptoms, and we could potentially modify return to sport or any other protocols based on what we’re seeing with imaging,” Conway Kleven said. “We can’t claim that with this study, but that’s where future studies could go, based on what we found.”

More Research Needed

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Munro Cullum, PhD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neurologic surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, noted that while the findings are an important step, much work remains before the NINDS research criteria can be used in the clinic.

“It represents a step in the right direction as one of the first studies to apply the new criteria in a population, but it really doesn’t help validate the TES diagnosis,” Cullum said.

A more detailed look at the effects of age, education, length of exposure to repetitive head impacts from fighting as well as cognitive data and other factors related to brain volume and cognitive function are needed, he noted. Data on depression scores are also important to have.

“It’s great to see this work being done in this really unique population, but it raises a lot of questions for me,” he said.

The study was unfunded. Conway Kleven and Cullum report no relevant financial conflicts. Full disclosures are included in the original article.

Neurology. Published online June 28, 2023. Abstract

Kelli Whitlock Burton is a reporter for Medscape Medical News covering neurology and psychiatry.

For more Medscape Neurology news, join us on Facebook and Twitter.

Source: Read Full Article