How Old Is Too Old to Start Strength Training?

Aging may be the greatest threat to your freedom and independence you’ll ever know, only because of what it does to your muscles.

“The anabolic hormones that are responsible for maintaining muscle decline with age,” says Brandon Grubbs, PhD, assistant professor of exercise physiology and co-leader of the Positive Aging Consortium at Middle Tennessee State University. “Older adults also tend to be less active and consume less protein, which is important for muscle mass.”

Not only that, but the “satellite cells” responsible for muscle repair become less responsive, says Grubbs, and the muscle fibers hold on to fewer of them. So growing muscle gets harder too.

Research shows we begin losing muscle around age 35, and the process picks up after we hit 60. While many of us are dreaming up fun plans for retirement, we’re also losing as much as 3% of our muscle per year.

But the loss of muscle due to aging, known as sarcopenia, affects more than your reflection in the mirror. It can greatly influence your health and well-being.

Sarcopenia has been linked to type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity. It may increase the risk for heart disease and stroke, and take years off your life. It also jeopardizes your freedom to live on your own, not to mention travel, spend time with grandkids, or do so many of the things that make older adulthood joyful and fulfilling.

“Physical frailty,” says Grubbs — that is, weakness, slowness, unintentional weight loss, and fatigue — “is intertwined with sarcopenia.” If your body starts wasting, so does your ability to go about your daily life and do things you enjoy.

Luckily, there is a powerful remedy: lifting weights.

“Strength training mitigates the loss of muscle function that occurs with age,” says Grubbs. “It stimulates muscle growth and enhances muscle tissue quality, meaning you can generate more force with a given amount of muscle.”

Strength training boosts connective tissue strength and bone mineral density, Grubbs adds. “It can extend someone’s ability to remain living independently and reduce the risk of falls and fractures. It’s also good for one’s psychological well-being.”

Yet, only 9% of people over 75 perform strength training regularly — that is, at least two times per week. It’s not hard to see why.

Strength training can be intimidating for anyone, especially if you’re north of 60 and you’ve never held a dumbbell in your life. Health problems, pain, fatigue, fear of injury — all can keep older adults out of the weight room. Other barriers include a lack of social support and available exercise facilities.

But here’s the thing: Being old by itself is not a limiting factor — so it’s no excuse to avoid exercise. Actually, nothing is.

Both the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommend strength training for older adults, noting that programs can be adapted for those with frailty or chronic conditions.

That’s not news. The ACSM’s original Position Stand on Exercise and Physical Activity for Older Adults put it plainly: “In general, frailty or extreme age is not a contraindication to exercise, although the specific modalities may be altered to accommodate individual disabilities.” The presence of disease states commonly associated with aged populations — ranging from arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes to dementia, osteoporosis, and stroke — “is not by itself a contraindication to exercise” either, even if all are present within a single individual.

“For many of these conditions,” says the ACSM, “exercise will offer benefits not achievable through medication alone.” And despite the common fear of pain or injury: “Sedentariness appears a far more dangerous condition than physical activity in the very old.”

A 2022 study found that healthy older men who lifted weights strengthened the connections between their nerves and muscles, helping them maintain physical function. The subjects’ average age was 72, but they were just kids compared to participants in a landmark 1990 trial that looked at frail, institutionalized people as old as 96.

The study was small — just 10 participants — but significant because of their age (86 to 96) and the remarkable results: After 8 weeks of resistance training, they improved their strength by 174% while adding 9% more muscle to their mid thighs. These were residents of a long-term care facility; they were not acutely ill but not especially healthy, either. One 86-year-old man stopped at 4 weeks due to a “straining sensation during training at the site of a previously repaired inguinal hernia,” the study notes. “The attendance rate was 98.8% for the 8-week program in the 9 subjects who completed the study. No cardiovascular complications were seen.”

“That study demonstrated that even the oldest of the old can improve strength and muscle mass,” says Grubbs. “I’m not aware of an age where one can’t improve those outcomes.

“There are bodybuilders who still compete in their 70s,” Grubbs adds. “Older adults don’t gain muscle and strength as well as younger ones — the training response may be slower — but significant improvements in strength and muscle can be achieved with the right program.”

Okay, So What Is the “Right” Strength Program for Older Adults?

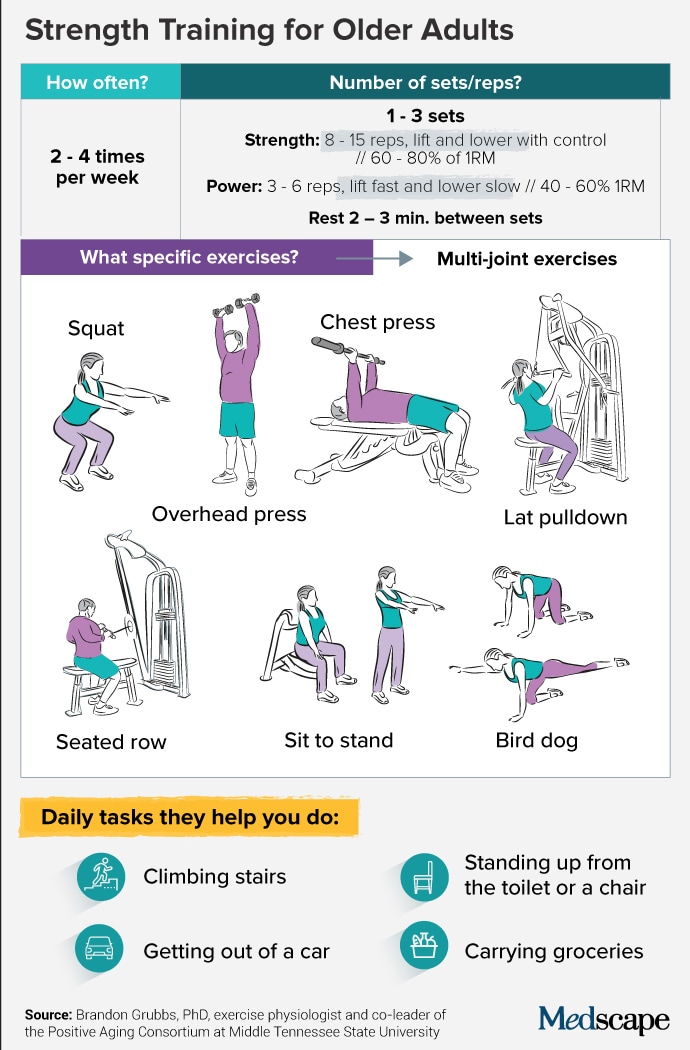

The ACSM recommends that people ages 65 and up train two to four times per week in sessions lasting 30 to 60 minutes. Grubbs says just one workout per week is enough to start; a 2019 study in participants over 75 suggests that as little as an hour of strength training per week can improve walking speed, leg strength, and one’s ability to stand up out of a chair.

Trainees should perform one to three sets of 8 to 15 repetitions per exercise, going as heavy as 80% of their “one-repetition maximum,” or one-rep max (the greatest amount of weight you can lift one time). A one-rep max is difficult and potentially dangerous to test, so it’s OK to estimate it conservatively. (Really, you just want a weight you can lift 8 to 15 times that’s challenging enough but not so heavy that you sacrifice proper form.)

Do multi-joint exercises, Grubbs recommends — traditional strength moves like the squat, overhead press, chest press, seated row, and lat pulldown. These better prepare you for the activities of daily living than isolation exercises (those that target a specific muscle) or machine movements do — although machines may be more appropriate for people with balance issues or other difficulties that make multi-joint, free-weight exercises problematic.

Keep in mind that any move can be made easier to suit your fitness level. You may not need to drop into a deep squat if a quarter-squat (squatting only a quarter of the way) feels challenging enough.

Rest between sets can be 2 to 3 minutes.

Focus on Power Training

Interestingly, while traditional resistance training will build muscle and strength, Grubbs suggests that older adults focus more on power — the skill of applying force quickly. “Power is better related to older adults’ ability to perform activities of daily living,” he says, including walking speed, and going from sitting to standing.

In fact, a 2022 review showed that power training may be more effective than traditional strength training in improving older adults’ “functional performance.” Meaning you’ll have an easier time climbing stairs, getting out of a car, and standing up from a chair or the toilet.

The good news is power training is no more complicated than strength work, and it actually feels less challenging. With power, speed of movement is the focus, so you choose a light weight — around 40% to 60% of your one-rep max, or really any load you can move quickly — and lift it as fast as you can (but safely, and with control). Take a second or two to lower the weight and reset. Repeat for three to six repetitions, or until you feel your form may be compromised, or you’ve lost significant speed. Do one to three sets.

What kind of moves are “power” moves? You can do the same ones you use for strength, just faster. If you want to maximize your results, Grubbs says you can cycle your workouts, keeping the same movements but changing the speed at which you perform them and the level of weight you use to build muscle, strength, and power. For instance, you can train with heavier weights one day to focus more on strength, and then use lighter weights with faster rep speeds in your next workout to promote power. Keep going back and forth from there.

According to Laura Grissom, the Health and Wellness Education Coordinator at St. Clair Senior Center in Murfreesboro, TN, one exercise that all older adults should practice is the “sit to stand,” which is just what it sounds like.

“Sit at the edge of a chair, with your feet on the floor, and cross your arms over your chest,” says Grissom. “Lean back until your back touches the back of the chair, brace your abs, and then come forward and stand up.” That’s one rep. Take it easy at first, with three sets of 10, and then work on doing it faster, as power training.

How to Get Started

If you’re brand-new to exercise, you may consider working with a physical therapist, who can help you come up with a customized plan, educate you on proper form, and advise how hard you should be working. If you have a medical condition, talk to your doctor, too. Medicare may cover physical therapy with a doctor’s referral.

A personal trainer can be great if you have the budget. (Some are specially certified to train older adults, such as those with the National Academy of Sports Medicine’s Senior Fitness Specialization.) But if not, look into group fitness classes like the kind Grissom runs. Your local senior center may offer them, Grissom says. You can also search for a SilverSneakers class near you. Designed just for adults 65-plus, SilverSneakers fitness programs are available in thousands of gyms and community centers nationwide (and virtually via Zoom), and the cost is covered by many Medicare plans.

Working out in a group setting may be one of the best ways to see that you continue to work out at all. A study in Health Psychology found that adults 65 and up who exercised together in a program designed to foster a sense of social connectedness had greater adherence to their workouts.

“People don’t come to our seniors’ classes just to exercise,” says Grissom. “It’s a social event. When a person is retired, they find themselves with more time on their hands and not around other people as much. But when they come to class, they make friends and have accountability. If someone doesn’t show up to a class a couple of times, someone else in the class is going to call them and ask if everything’s OK. Once they get into the camaraderie of the classes, most people come back again.”

Seeing the benefits can help keep you motivated, as well.

“So many people have told me over the years that they’ve been able to stop taking medication because they came to my class,” says Grissom. “They’ll say, ‘My blood sugar and cholesterol went down…. The pain in my shoulder went away….’ If you have a health problem, the best thing you can do is exercise.”

No matter how old you are.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article