What’s the Difference Between Fructose and Glucose?

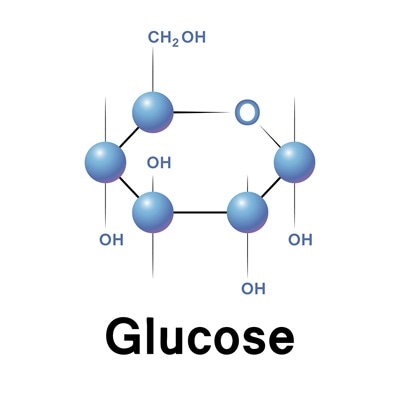

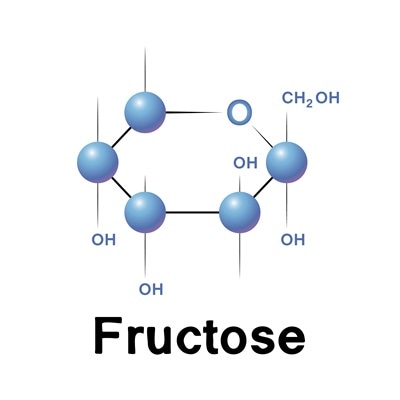

Fructose and glucose are both simple monosaccharide sugars. Both starch and sugar, whether sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup (HCFS), yield glucose in large amounts when digested.

Glucose is absorbed and transported directly to the body cells to fuel their metabolism, and to eventually form water and carbon dioxide through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. It does not undergo any hepatic uptake, and in a state of excessive energy intake, another pathway is used to store it in the form of glycogen, and a third is to be converted to fatty acids and deposited in fat tissue in the form of triglycerides.

When the excessive ingestion of energy becomes chronic, both muscle and fat cells become insulin resistant and glucose uptake at the periphery becomes less, leading to increased insulin secretion as the cells demand more glucose supply. This leads finally to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Fructose has a low glycemic index (GI) of only 23, compared to glucose (and used as the standard) which has a GI of 100. Its ingestion is followed by rapid absorption which leads to a small postprandial rise in blood glucose. However, the liver is the main site of fructose metabolism, where fructose is converted to fructose-1-phosphate, thereby proving that it is not subject to phophofructokinase regulation, which is the main rate-limiting step in the metabolism of glucose.

This means that the amount of acetyl CoA and glycerol-3-phosphate (byproducts of this metabolism, and also fatty acid precursors) entering the liver cells is unregulated, and therefore unrestricted lipogenesis is possible. Moreover, the fructose activates genes which activate lipogenesis such as fatty acid synthase and acetyl CoA carboxylase, independent of insulin. In other words, fructose can end up as glucose, fatty acids or as lactate. Sucrose, HCFS, honey and fruit all yield significant amounts of fructose.

This is due to the transformation of some of the fructose to glucose. Fructose metabolism bypasses an important step in glucose processing, namely the rate-limiting conversion of glucose to glucose 1,6 biphosphate via the enzyme phosphofructokinase. This in turn means that insulin secretion is not activated directly.

The body is thus not aware of the increased availability of a monosaccharide sugar in large quantities, unlike the situation when glucose is digested. There is also no signal to show that a positive energy status has been attained, in the form of increased ATP and citrate within the cells (as occurs with glucose metabolism), to limit fructose uptake by the liver and its conversion to fat. This is one explanation of why both fructose and glucose lead to obesity.

Both fructose and glucose limit subsequent eating behavior in a similar fashion, and are thus important in appetite regulation. Both cause ghrelin lowering, GLP-1 to increase and cholecystokinin to change similarly even though one produces a much smaller rise in blood glucose and insulin levels than the other.

One study showed that consuming beverages sweetened with fructose but not glucose over a period of 10 weeks led to the synthesis of fat in the liver, increased blood lipid levels above normal levels, reduced the person’s sensitivity to insulin, and led to increased central deposition of fat in subjects who were overweight or obese.

In contrast, glucose typically leads to fat deposition in the subcutaneous tissue. It is important to realize that individual differences are present and marked in the response of fasting triglyceride levels to ingested fructose.

Fructose leads to de novo fat synthesis even when it is taken in quantities that fit the total recommended energy intake diet for the subject.

The changes in lipid metabolism associated with fructose ingestion include increased synthesis of fatty acids from fructose, inhibition of oxidation of fatty acids from the circulation, and thus increased secretion of VLDL from the liver.

This postprandial hypertriglyceridemia is even more marked in obese subjects who are in a state of positive energy balance.

Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity is also inhibited in these subjects leading to increased subcutaneous fat deposition. LPL inhibition is thought to be due to decreased postprandial insulin secretion and sensitivity, since insulin activates LPL.

It is noticeable that fatty tissue in the skin is more sensitive to insulin, and therefore to glucose consumption, while the lack of this insulin effect causes visceral fat deposition.

Hepatic insulin resistance in fructose is likely to be due to de novo lipogenesis and thus flooding the liver with intrahepatic fat particles, rather than by increasing free fatty acid levels in the portal and systemic circulation by adipose tissue deposition and adipose insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance is more profound in response to fructose in females, but visceral fat deposition is more pronounced in males.

This may confirm that the insulin resistance induced by fructose acts independent of visceral fat and of free fatty acid levels in blood.

Increased postprandial hypertriglyceridemia is important because it predisposes to atherogenesis. Moreover, the lipid particles produced are smaller and hence more susceptible to oxidation than the larger LDL particles, which means that fructose consumption leads to increased levels of oxidized LDL. If the subject is already hyperlipidemic, including more than 25% of fructose as a source of energy in the diet may worsen this risk factor.

Another result from experimental study shows that fructose ingestion reduces leptin levels unlike glucose. This means that over the long term, consuming excessive fructose can cause a positive energy balance and lead to obesity.

On the other hand, substituting about 6-12% (30-60g) of total energy in the diet with fructose may benefit by reducing the glucose levels without affecting lipid parameters negatively, but higher levels (20%) may lead to increased VLDL/LDL levels, significantly more in hyperinsulinemic subjects.

Thus a high-fructose diet can induce the metabolic syndrome in subjects with the greatest changes occurring in those who are at the highest risk for ischemic heart disease.

So, is it better to consume glucose or fructose as a source of energy? Current knowledge would say that both are useful and healthy only when taken in minimal amounts, as a source of sweetness only when needed.

Most energy in the diet should come from complex carbohydrates such as whole fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and judicious amounts of whole milk in different forms, butter and vegetable fat, the whole combined with plenty of water, physical activity and stress relief in ways that build up the mind and body.

Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2673878/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17593904

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3037017/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2682989/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2714385/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24370846

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991323/

Further Reading

- All Fructose Content

- All Glucose Content

- What is HbA1C Testing?

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article