What is Listeriosis?

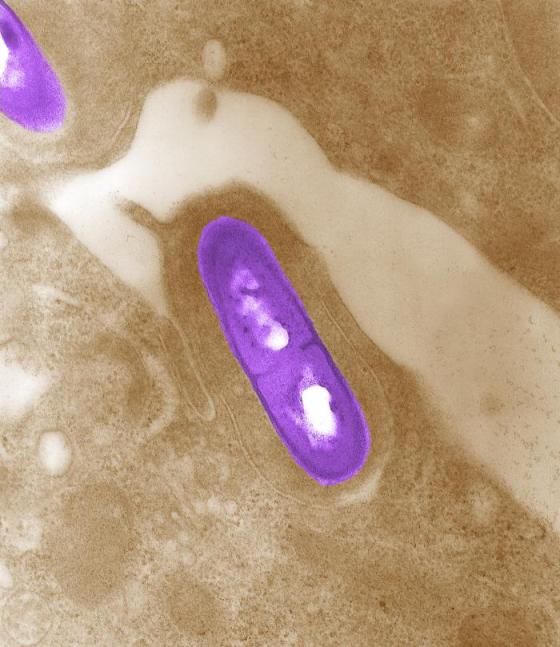

Despite having a low occurrence rate, Listeria monocytogenes represents one of the most prominent foodborne pathogens in the world. This opportunistic gram-positive bacillus is able cross three host barriers: the intestinal, blood-brain and placental. Unlike most other foodborne pathogens, Listeria can successfully grow in food with fairly low moisture content and high salt concentration.

Fecal carriage and serologic assessment indicate that although many individuals are exposed to Listeria monocytogenes, only a few develop invasive infection. Most infections are observed in neonates, older adults, pregnant women and those with immunocompromising conditions, which are all groups where listeriosis can manifest as a severe illness – including bacteremia, meningitis, fetal loss, and death.

Incubation and clinical picture

The incubation period for listeriosis varies according to the clinical presentation of the disease and ranges from three days to 70 days. A shorter incubation period is observed in non-invasive form of the disease, whereas much longer period is often found in pregnancy-associated cases and invasive forms.

In otherwise healthy people, the infection with Listeria monocytogenes most often leads to acute febrile gastroenteritis, which is usually mild and self-limiting. In pregnancy, the most common manifestation of listeriosis is bacteremia, classically accompanied by an episode of flu-like illness with fever, myalgia and headache.

Neonatal listeriosis can be divided into early and late onset groups, with the former being defined as sepsis manifesting within 5 days of birth and classically presenting as granulomatosis infantisepticum (characterized by widely disseminated granulomas in several organs). On the other hand, infants who manifest the late onset form are usually healthy at birth, but after a period of 14 days develop meningitis or meningoencephalitis.

According to clinical presentation, adult invasive listeriosis can be categorized into three groups: central nervous system (CNS) disease which accounts for as much as 75% of all cases, primary bacteremia and a miscellaneous group which encompasses a wide array of diverse localized infections.

The most common non-meningitic form of CNS listeriosis is encephalitis, most frequently affecting the rhombencephalon. A myriad of other clinical syndromes that are associated with invasive adult listeriosis are osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, hepatic abscesses, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, endocarditis, and rare ocular infections that can be sight threatening.

Establishing a diagnosis

Diagnosis of listeriosis on clinical grounds alone is often cumbersome, partly because pathognomonic signs are scarce, and partly because it is a rare infection and often not considered in differential diagnosis. Furthermore, Listeria monocytogenes may be misidentified in the clinical laboratory for various reasons.

Gram staining of specimens from normally sterile sites may suggest a diagnosis of listeriosis, as short gram-positive rods are seen in bot intracellular and extracellular locations. Nevertheless, the bacteria may appear coccoid, filamentous or even gram-negative, especially in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with partially treated meningitis.

A large array of systems which detect listerial antigens – such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or reversed passive latex agglutination – have been developed, but mostly for the identification of Listeria in food. Thus isolation of this pathogen and identification of characteristic biochemical reactions is most often enough for presumptive identification, which should be confirmed with specific manual or automatic identification systems.

Detection of antibodies has occasionally proved useful in the identification of outbreaks, as well as in seroprevalence studies, but a fourfold rise in titer is required for definitive diagnosis. Unfortunately, in sporadic cases, acute sera are rarely available by the time listeriosis is suspected.

Sources

- http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/11

- www.oie.int/…/2.09.07_LISTERIA_MONO.pdf

- www.gov.uk/…/ID_3i3.1.pdf

- jmm.sgmjournals.org/…/pdf

- Kerr KG. Listeria and Erysipelothrix spp. In: Gillespie S, Hawkey PM, editors. Principles and Practice of Clinical Bacteriology. John Wiley & Sons, 2006; pp. 139-158.

- Edwards MS. Listeriosis. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis C, Jones MD, editors. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles & Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006; pp. 1079-1081.

Further Reading

- All Listeriosis Content

- Listeriosis Epidemiology

- Listeriosis Treatment

Last Updated: Aug 23, 2018

Written by

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović is a medical doctor (MD) with a Ph.D. in biomedical and health sciences, specialist in the field of clinical microbiology, and an Assistant Professor at Croatia's youngest university – University North. In addition to his interest in clinical, research and lecturing activities, his immense passion for medical writing and scientific communication goes back to his student days. He enjoys contributing back to the community. In his spare time, Tomislav is a movie buff and an avid traveler.

Source: Read Full Article