Diagnosis of Granuloma Inguinale (donovanosis)

Granuloma inguinale (also known as donovanosis) represents a granulomatous, slowly progressive ulcerative disease that is caused by Calymmatobacterium granulomatis (recently reclassified as Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov.). The disease may persist for years and lead to serious complications. The diagnosis is often made on clinical grounds due to the fastidious nature of the causative agent.

Clinically, the condition has to be distinguished from other sexually-transmitted causes of genital ulcer disease, most notably syphilis, chancroid and large herpetic ulcers. If necrosis and/or tissue destruction are present, amebiasis and penile carcinoma should also be considered. Furthermore, a history of travelling and sex in an endemic country should also raise suspicion when evaluating patients in developed countries.

Direct Microscopy

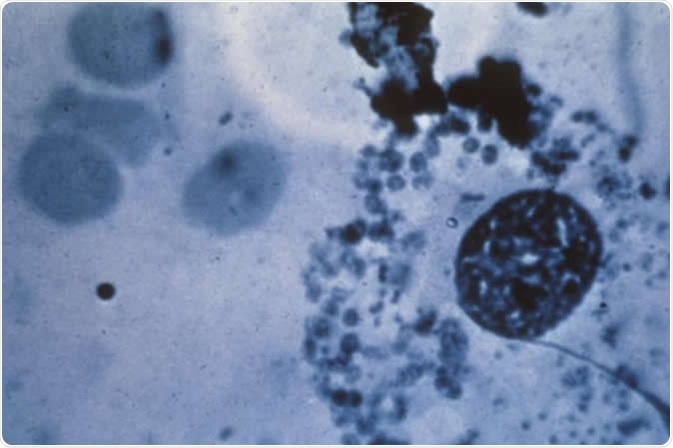

Direct microscopic analysis of tissue smears still represents a cornerstone of diagnostic appraisal. The key is to observe adequately stained Donovan bodies (intracellular bacteria), so most diagnostic centers have developed their own methods to maximize the diagnostic yield.

Classical approach is a slow overnight staining by Giemsa method, Leishman’s stain or Wright’s stain. Before that the specimen has to be obtained by means of a forceps, currette, or the edge of a safety razor blade, and then crushed between two slides.

A modified Giemsa stain (also known as RapiDiff) is known to give rapid results in a busy clinical milieu. The organisms stained this way are ovoid and pleomorphic, with pink capsule and bluish/purple body. Donovan bodies have also been observed in Papanicoulau smears.

In more high-tech laboratories, a transmitting electron microscopy may be used for the evaluation of the ultrastructural features of Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. In endemic areas indirect immunofluorescence also plays a role, albeit the evidence for firm diagnosis is lacking.

Culture and Histopathology

After the initial report that described culturing Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. from feces in 1962, there was a gap of 35 years without any successful attempts. However, in 1997 in Durban the putative microorganism was shown to grow and divide in a monocyte co-culture system from biopsy specimens (after specific pretreatment with antimicrobial amikacin). Modified chlamydia culture was also used for culturing purposes.

For lesions that are small, sclerotic, dry or necrotic, there is often a need for biopsy and subsequent histological examination. Giemsa and silver staining are most efficient for visualizing the microorganisms in tissue sections. The characteristic histological finding reveals chronic inflammation with a preponderance of polymorphonuclears and plasma cells (which can be also found in the epidermis).

Molecular Techniques

Although the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is a molecular diagnostic tool, in diagnosing granuloma inguinale has been reported, the technique is still mostly available as a research tool. Amplification of Klebsiella-like sequences was initially achieved by using primers that target the phoE gene.

Later a diagnostic PCR tool was developed from the observation that two unique base changes in the aforementioned gene eliminate HaeIII restriction sites, which enables clear distinction from closely related Klebsiella species. This method was then further refined into a colorimetric PCR test that is becoming ever-more pervasive in diagnostic microbiology laboratories.

Recently introduced was also a multiplex PCR that targets genital ulcers, and hence includes Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. alongside Treponema pallidum (causative agent of syphilis), Haemophilus ducreyi (causative agent of chancroid) and herpes simplex viruses.

Sources

- http://www.antimicrobe.org/b108.asp

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26882914

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11394976

- https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000636.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1758360/

- www.scielo.br/scielo.php

- Lupi O, Chicralla P, Martins CJ. Donovanosis. In: Gross G, Tyring SK, editors. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Springer Science & Business Media, 2011; pp. 191-196.

- O’Farrell N. Donovanosis. In: Kumar B, Gupta S, editors. Sexually Transmitted Infections, Second Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014; pp. 533-541.

Further Reading

- All Granuloma inguinale Content

- Clinical Presentation of Granuloma Inguinale (Donovanosis)

- Granuloma Inguinale (Donovanosis)

- Treatment of Granuloma inguinale (Donovanosis)

- Epidemiology of Granuloma Inguinale (Donovanosis)

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019

Written by

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović

Dr. Tomislav Meštrović is a medical doctor (MD) with a Ph.D. in biomedical and health sciences, specialist in the field of clinical microbiology, and an Assistant Professor at Croatia's youngest university – University North. In addition to his interest in clinical, research and lecturing activities, his immense passion for medical writing and scientific communication goes back to his student days. He enjoys contributing back to the community. In his spare time, Tomislav is a movie buff and an avid traveler.

Source: Read Full Article