Two weeks into Melbourne’s lockdown, why aren’t COVID-19 case numbers going down?

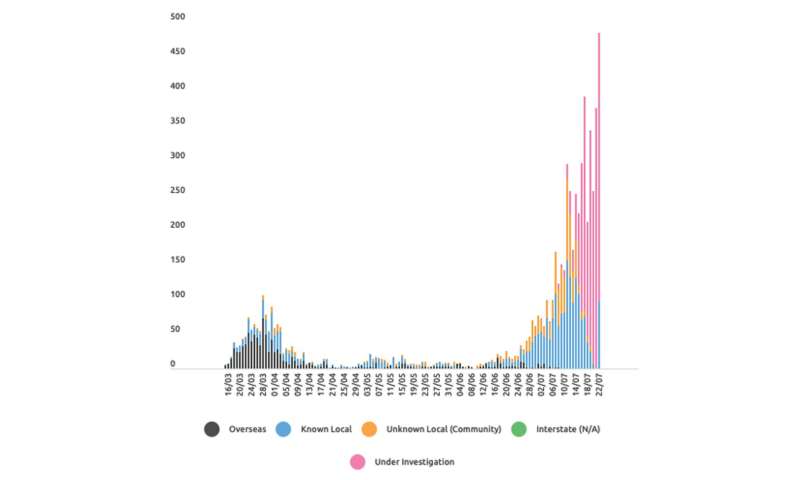

Fourteen days after Melbourne was put back into lockdown, the latest daily tally of 484 new cases in Victoria makes for dispiriting reading. Why have the numbers stubbornly refused to go down, despite Melburnians being confined to their homes for all but non-essential trips?

The first lockdown, imposed nationwide in March and April, was largely successful in containing the coronavirus. However, the subsequent relaxing of restrictions, a lack of adherence to social distancing and a breach in hotel quarantine led to a second wave of infections in Melbourne. Lockdown conditions were reintroduced on July 9 after the daily case count rose to 191.

Addressing the media today, Premier Daniel Andrews said a “dramatic improvement” was needed in aspects of the public’s behaviour, pointing the finger specifically at people who had not self-isolated between developing symptoms and getting a COVID-19 test.

Melbourne’s second lockdown—the story so far

After a brief lockdown of specific postcodes beginning on July 1, the whole of metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell Shire were put into a second lockdown from July 9, for a minimum of six weeks, in a bid to suppress the continued high rates of new cases.

The “stage 3” restrictions, covering roughly 5 million residents, require people to stay at home unless shopping for food and supplies, travelling for care and caregiving, exercising, or commuting to study or work if they can’t be done from home.

From midnight tonight, face covering is also mandatory when outside the home.

Why haven’t case numbers dropped?

These lockdown measures have now been in place for 14 days—the upper limit of the coronavirus’s incubation period in most cases. So why haven’t the case numbers tapered off? There are a few reasons.

First, this second wave has a much larger proportion of cases that have arisen via community transmission with currently almost half of all local cases having an unknown contact or still being under investigation. These are harder to control because the source of infection is unknown, which makes the process of testing, tracing and isolating known contacts of confirmed cases harder.

While in the first two weeks we will see a decline or at least stabilisation of the numbers of cases in each known cluster, those untraced contacts and asymptomatic individuals may continue to spread the virus and start up new clusters.

Second, the current restrictions still allow significant movement of people between suburbs and to work. Face-to-face teaching in schools is still permitted, and there is no limit on the number of people in supermarkets and shopping centres.

Third, the virus has mutated and the new mutated form spreads much faster. This could be a factor in this second wave, although this is far from certain.

Fourth, some people still may not grasp the full seriousness of the situation and the need to help stop the spread—perhaps having been persuaded by misinformation on social media.

Fifth, each renewed measure of restriction increases the fatigue in the population, meaning more people may struggle to stick to the guidelines.

Finally, new evidence suggests COVID-19 is more severe in colder months than warmer ones, and that dry indoor air may encourage the spread of the disease. Again, it’s not clear how strong a factor this is in Melbourne.

For these reasons, we believe the current interventions are not sufficient. However, the impact of the added facial covering requirement will not be immediately apparent, and is hard to distinguish when combined with all the other measures.

What further measures are available?

Melbourne temporarily imposed a stage 4 lockdown of nine public housing blocks, under which residents were not allowed to leave, and had to rely on deliveries of food and medicines.

Similarly, New Zealand’s level 4 lockdown in March and April included strict stay-at-home requirements and the closure of all non-essential businesses and educational facilities. These strict measures were lifted on April 27, and the government declared COVID-19 eliminated from New Zealand on June 8.

Arguing for Melbourne to achieve elimination, researchers led by Tony Blakely of the University of Melbourne recently published a list of recommendations to increase restrictions during the city’s current six-week lockdown. Suggested measures include:

- continue with the present restrictions and hygiene advice

- close all schools

- tighten the definition of essential shops that can remain open.

- tighten the definition of essential workers and essential businesses

- restrict travel only to essential businesses

- require correct mask-wearing

- further strengthen testing and contact tracing

- extend the suspension of international arrivals into Victorian quarantine.

These enhanced measures should ideally stay in effect for at least 4-6 weeks, to allow cases to fall to almost zero and remain at that level for at least two weeks.

Besides reducing infections, hospitalisations and deaths, this approach could also foster a greater sense of safety among the community, potentially allowing a faster economic recovery once restrictions are lifted.

Currently Australia is pursuing a suppression strategy which heavily relies on the compliance of the population with the restrictions imposed. This strategy allows for low levels of cases in the community, which in turn brings a continued risk of renewed outbreaks.

The prospect of ongoing, repeated lockdowns would take a toll not only on the economy but also on the mental and physical health of the population.

What are the criteria for ending or renewing a lockdown?

There are no hard-and-fast rules, so ultimately this is a question of political judgement. In May, the federal government published a three-step roadmap to easing restrictions, but left the precise criteria and timelines to the discretion of state and territory leaders.

Similarly, the World Health Organisation’s list of key considerations for lifting restrictions are broad and generic. For instance, countries must ensure coronavirus transmission is “controlled”, but there is no formal definition of this.

In Germany, which is not pursuing an elimination strategy, the threshold for imposing a new lockdown is set at 50 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants accumulated over seven days. However, for an elimination strategy this threshold would need to be set at zero new cases for two weeks, as was done in New Zealand.

Source: Read Full Article