The Lancet: More nurses lead to fewer patient deaths&readmissions, shorter hospital stays, and savings

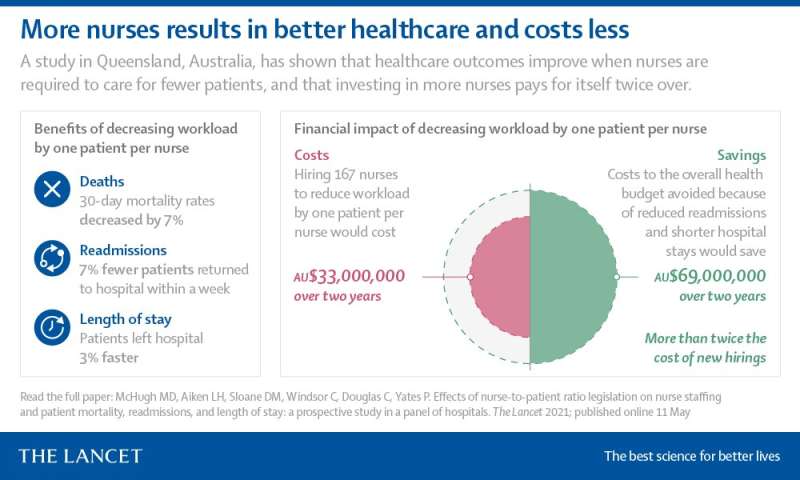

A study across 55 hospitals in Queensland, Australia suggests that a recent state policy to introduce a minimum ratio of one nurse to four patients for day shifts has successfully improved patient care, with a 7% drop in the chance of death and readmission, and 3% reduction in length of stay for every one less patient a nurse has on their workload.

The study of more than 400,000 patients and 17,000 nurses in 27 hospitals that implemented the policy and 28 comparison hospitals is published in The Lancet. It is the first prospective evaluation of the health policy aimed at boosting nurse numbers in hospitals to ensure a minimum safe standard and suggests that savings made from shorter hospital stays and fewer readmissions were double the cost of hiring more staff.

Despite some evidence that more nurses in hospitals could benefit patient safety, similar policies have not been widely implemented across the globe, partly due to an absence of data on the long-term effects and costs, as well as limited resources. In recent years, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland have mandated numbers of patients per nurse, but strategies to improve nursing levels remains debated worldwide.

“Our findings plug a crucial data gap that has delayed a widespread roll-out of nurse staffing mandates. Opponents of these policies often raise concerns that there is no clear evaluation of policy, so we hope that our data convinces people of the need for minimum nurse-to-patient ratios by clearly demonstrating that quality nursing is vital to patient safety and care”, says lead author, Professor Matthew McHugh of the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, USA.

In 2016, 27 public hospitals in Queensland were required to instate a minimum of one dedicated nurse for every four patients during day shifts and one for every seven patients for night shifts on medical-surgical wards.

The research team collected data from those 27 Queensland hospitals that instated ratios and from 28 other hospitals in the state that did not, at baseline in 2016 and at follow-up in 2018 (two years after the policy was implemented). Only nurses in direct contact with adult patients in medical-surgical wards were included—data from patients in birthing suites and psychiatric units were not assessed in the study.

Researchers used patient data to assess demographics, diagnoses, and discharge details for patients, as well as length of hospital stay. These data were then linked to death records for 30 days following discharge, and to readmissions within seven days of discharge.

The researchers sent an email survey to nurses in each hospital to ask about the numbers of bedside nurses and patients on their most recent shift. The responses were used to establish the numbers of nurses per patient and then averaged across wards and hospitals. Responses were received from 8,732 nurses (of a possible 26,871) at baseline in 2016, and 8,278 (of a possible 30,658) in 2018.

The study includes baseline data for 231,902 patients (142,986 in hospitals that implemented the policy and 88,916 in comparison hospitals), and for 257,253 patients (160,167 in hospitals that implemented the policy and 97,086 in comparison hospitals) after the policy was brought in.

Comparison hospitals had no change in staffing, with six patients per nurse in 2016 and the same ratio (1:6) in the follow-up period in 2018. Intervention hospitals averaged five patients per nurse at baseline in 2016, with a reduction to four per nurse after the policy implementation.

To compare the changes in outcomes in the intervention and comparison hospitals over time, the researchers estimated the odds of dying within 30 days of admission and of being readmitted within seven days of discharge, and the additional length of stay, after adjusting for factors such as patient age, sex, existing health conditions and hospital size. They found that the chance of death rose between 2016 and 2018 by 7% in hospitals that did not implement the policy, and fell by 11% in hospitals that did implement the policy.

The chances of being readmitted increased by 6% in the comparison hospitals over time, but stayed the same in hospitals that implemented the policy. Between 2016 and 2018, the length of stay fell by 5% in the hospitals that did not implement the policy, and by 9% in hospitals that did.

Further analyses found that when nurse workloads improved by one less patient per nurse, the chance of death and readmissions fell by 7%, and the length of hospital stay dropped by 3%.

Using their modelling to predict figures that would have been expected without the policy in place, the researchers estimated that there could have been 145 more deaths, 255 more readmissions and 29,222 additional days in hospital in the 27 hospitals that implemented the policy between 2016 and 2018.

To calculate the financial impact of the staffing policy, the researchers used state data to estimate the cost of funding the 167 extra staff needed to reduce workload by one patient per nurse at approximately $33,000,000 (AUD) in the first two years. Based on Australian health economic data, they further estimated that preventing readmissions and reducing lengths of stay resulted in an approximate saving of $69,150,858 in the 27 hospitals across the two years following the mandate.

“Part of the reluctance to bring in a minimum nurse-patient ratio mandate from some policy-makers is the expected rise in costs from increased staffing. Our findings suggest that this is short-sighted and that the savings created by preventing readmissions and reducing length of stay were more than twice the cost of employing the additional nurses needed to meet the required staffing levels—a clear return on investment. Often, policy-makers are concerned about whether they can afford to implement such a policy. We would encourage governments to look at these figures and consider if they can afford not to,” says Professor Patsy Yates of the Queensland University of Technology School of Nursing, Australia. [1]

The authors note that there are a number of limitations associated with the study. Hospitals in the research were not randomly assigned to comparison or intervention groups, as only 27 hospitals in the state were mandated to follow the policy. Furthermore, the hospitals included in both groups were not matched for size or patient demographics and health conditions, although this is accounted for in adjusted analyses.

Source: Read Full Article