Study Finds Sharp Drop in Opioid Scripts Among Most Specialties

The volume of prescription opioids dispensed at retail pharmacies in the United States dropped by 21% in recent years amid efforts to reduce unnecessary use of the painkillers, but the rate of decline varied greatly among types of patients and by type of clinician, a study found.

In a brief report published December 28 by the Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers from the nonprofit RAND Corp reported an analysis of opioid prescriptions from two periods, 2008–2009 and 2017–2018.

Dr Bradley Stein

The researchers sought to assess total opioid use rather than simply track the number of pills dispensed. So they used days’ supply and total daily dose to calculate per capita morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for opioid prescriptions, write Bradley D. Stein, MD, PhD, MPH, the study’s lead author and a senior physician researcher at RAND Corp, and his co-authors in their paper.

For the study, the researchers used data from the consulting firm IQVIA, which they say covers about 90% of US prescriptions. Total opioid volume per capita by prescriptions filled in retail pharmacies decreased from 951.4 MME in 2008–2009 to 749.3 MME in 2017–2018, Stein’s group found.

(In 2020, IQVIA separately said that prescription opioid use per adult in this country rose from an average of 16 pills, or 134 MMEs, in 1992 to a peak of about 55 pills a person, or 790 MMEs, in 2011. By 2019, opioid use per adult had declined to 29 pills and 366 MMEs per capita.)

The RAND report found substantial variation in opioid volume by type of insurance, including a 41.5% decline (636.5 MME to 372.6 MME) among people covered by commercial health plans. That exceeded the 27.7% drop seen for people enrolled in Medicaid (646.8 MME to 467.7 MME). The decline was smaller (17.5%; 2780.2 MME to 2294.2 MME) for those on Medicare, who as a group used the most opioids.

“Almost Functions as a Rorschach Test”

The causes of the decline are easy to guess, although definitive conclusions are impossible, Stein told Medscape Medical News.

Significant work has been done in recent years to change attitudes about opioid prescriptions by physicians, researchers, and lawmakers. Aggressive promotion of prescription painkillers, particularly Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin, in the 1990s, is widely cited as the triggering event for the national opioid crisis.

In response, states created databases known as prescription drug monitoring programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 issued guidelines intended to curb unnecessary use of opioids. The guidelines noted how other medicines could treat chronic pain without raising the risk of addiction. The Choosing Wisely campaign, run by a foundation of the American Board of Internal Medicine, also offered recommendations about limiting use of opioids. And insurers have restricted access to opioids through the prior authorization process. As a result, researchers will make their own guesses at the causes of the decline in opioid prescriptions, based on their own experiences and research interests, Stein said.

“It almost functions as a Rorschach test,” he said.

Stein’s group also looked at trends among medical specialties. They found the largest reduction between 2008–2009 and 2017–2018 among emergency physicians (70.5% drop from 99,254.5 MME to 29,234.3 MME), psychiatrists (67.2% drop from 50,464.3 MME to 16,533.0 MME) and oncologists (59.5% drop from 51,731.2 MME to 20,941.4).

Among surgeons, the RAND researchers found a drop of 49.3% from 220,764.6 to 111,904.4. Among dentists, they found a drop of 41.3% from 22,345.3 to 13,126.1.

Among pain specialists, they found a drop of 15.4% from 1,020,808.4 MME to 863,140.7 MME.

Among adult primary care clinicians, Stein and his colleagues found a drop of 40% from 651,489.4 MME in 2008–2009 to 390,841.0 MME in 2017–2018.

However, one of the groups tracked in the study increased the volume of opioid prescriptions written: advanced practice providers, among whom scripts for the drugs rose 22.7%, from 112,873.9 MME to 138,459.3 MME.

Stein said he suspects that this gain reflects a change in the nature of the practice of primary care, with nurse practitioners and physician assistants taking more active roles in treatment of patients. Some of the reduction seen among primary care clinicians who treat adults may reflect a shift in which medical personnel in a practice write the opioid prescriptions.

Still, the trends in general seen by Stein and co-authors are encouraging, even if further study of these patterns is needed, he said.

“This is one of those papers that I think potentially raises as many questions as it provides answers for,” he said.

What’s Missing

Maya Hambright, MD, a family medicine physician in New York’s Hudson Valley, who has been working mainly in addiction in response to the opioid overdose crisis, observed that the drop in total prescribed volume of prescription painkillers does not necessarily translate into a reduction in use of opioids

“No one is taking fewer opioids,” Hambright told Medscape Medical News. “I can say that comfortably. They are just getting them from other sources.”

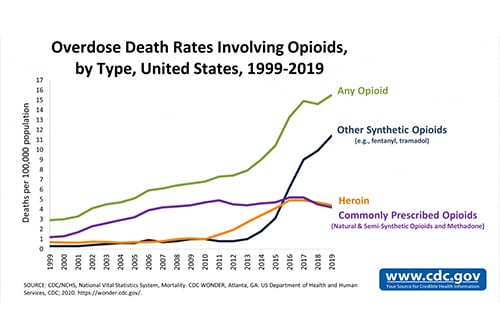

CDC data support Hambright’s view.

An estimated 100,306 people in the US died of a drug overdose in the 12 months that ended in April 2021, an increase of 28.5% from the 78,056 deaths during the same period the year before, according to the CDC.

Hambright said more physicians need to be involved in prescribing medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

The federal government has in the past year loosened restrictions on a requirement, known as an X waiver. Certain clinicians have been exempted from training requirements, as explained in the frequently asked questions page on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website.

(SAMHSA says legislation is required to eliminate the waiver. As of December 30, 2021, more than half of the members of the US House of Representatives were listed as sponsors of the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act (HR 1384), which would end the need for X waivers. The bill has the backing of 187 Democrats and 43 Republicans.)

At this time, too many physicians shy away from offering MAT, Hambright said.

“People are still scared of it,” she said. “People don’t want to deal with addicts.”

But Hambright said it’s well worth the initial time invested in having the needed conversations with patients about MAT.

“Afterwards, it’s so straightforward. People feel better. They’re healthier. It’s amazing,” she said. “You’re changing lives.”

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Stein and co-authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

Ann Intern Med. Published online December 28, 2021. Abstract

Kerry Dooley Young is a freelance journalist based in Washington, DC. She is the core topic leader on patient safety issues for the Association of Health Care Journalists. Young earlier covered health policy and the federal budget for Congressional Quarterly/CQ Roll Call and the pharmaceutical industry and the Food and Drug Administration for Bloomberg. Follow her on Twitter at @kdooleyyoung.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article